How Do Neck Gaiters Stack Up?

Face mask requirements have ramped up to reduce community spread of the COVID-19 virus, but we don’t hear much about which types are the most effective. A study published last week by Duke University researchers in Science Advances compared 14 types of face coverings and found that certain neck gaiters may actually do more harm than good.

Neck gaiters are thin, closed tubes of fabric that can be pulled up over the face, often used recreationally for warmth or to keep out wind and sand. But many have repurposed these as face coverings during the pandemic.

To evaluate mask efficacy, an individual wore each mask and spoke the same sentence in the direction of a laser beam within a dark enclosure. Droplets in the laser beam scatter light, which was recorded on a camera. A computer algorithm was used to count the droplets in the video, according to researchers.

Duke researchers tested 14 different face masks or mask alternatives and one mask material (not shown). Photo courtesy of Emma Fischer, Duke University.

The study results showed neck gaiters may amplify the number of respiratory droplets by acting like a sieve, creating more smaller droplets from larger ones. “Because smaller particles are airborne longer than large droplets (larger droplets sink faster), the use of such a mask might be counterproductive,” researchers said.

According to Martin Fischer, associate research professor in the Departments of Chemistry and Physics at Duke, it’s not the case that any mask is better than nothing.

“There are some masks that actually hurt rather than do good,” he said in a video produced by Duke. “You want to make sure when you wear a mask or go through the trouble of making a mask, you make one or wear one that actually helps — not just you — but helps everyone.”

The gaiter tested by the researchers was described in the study as a “neck fleece,” which was made from a polyester spandex material.

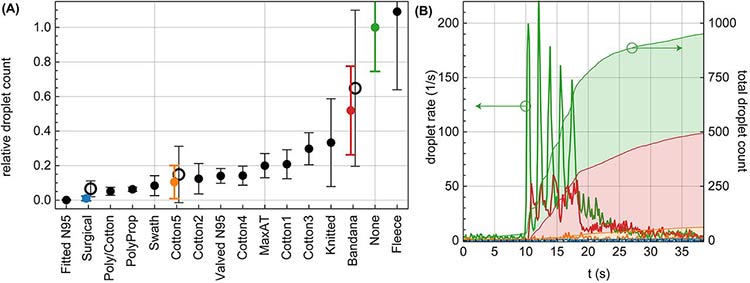

Of all the face coverings tested, the top performing was a fitted N95 mask, with droplet transmission below 0.1%. Following that was a three-layer surgical mask and then a handmade poly/cotton mask.

Droplet transmission through face masks. (A) Relative droplet transmission through the corresponding mask. Each solid data point represents the mean and standard deviation over 10 trials for the same mask, normalized to the control trial (no mask), and tested by one speaker. The hollow data points are the mean and standard deviations of the relative counts over four speakers. A plot with a logarithmic scale is shown in Supplementary Fig. S1. (B)The time evolution of the droplet count (left axis) is shown for representative examples, marked with the corresponding color in (A): No mask (green), Bandana (red), cotton mask (orange), and surgical (blue – not visible on this scale). The cumulative droplet count for these cases is also shown (right axis). Photo and caption courtesy of Duke University.

It’s important to note that mask testing in general has consistently shown that any face covering will block at least some droplets generated when we speak. More research is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of various types of masks.

“The jury is still out on whether neck gaiters cause more harm than good,” said Dr. John Greene, chair of the Infectious Diseases Program at Moffitt Cancer Center. “But we are encouraging everyone to wear any type of face covering, wash their hands and maintain social distancing to do their part to help stop the spread of the disease.”