Putting Faith in the Best Hands

For Jenna Morel, cancer feels like a weight.

The disease has weighed her family down for years. They first felt the weight in 2015, when Morel’s father died from lung cancer. It got heavier just six months later, when her mother was diagnosed with endometrial cancer. She died two years later.

“I thought after my mom passed we would have a break,” said Morel.

But that break never came. Morel was diagnosed with adrenocortical carcinoma — a rare cancer found in the outer layer of the adrenal gland — in April.

“When I was diagnosed, it was a very ‘why’ moment because both my parents died. Why me?” said Morel. “It was very hard.”

Morel's tumor was very large and quickly growing into her heart.

Even harder, Morel was just 34 years old, a mom to a 13-year-old and 2-year-old. She was in denial; she barely had any symptoms and still held onto hope the mass in her kidney could be easily removed.

But the cancer was advanced, and the tumor not only was the size of a football, but also was quickly growing into her heart.

Morel went to Moffitt Cancer Center, where a team of physicians would put together an extensive plan to try and save the young mother’s life.

Team Surgery

If Morel’s tumor wasn’t removed, she would most likely die within a year. Her only option was an extremely complex and risky surgery, and even if it were successful, there was a very high chance the cancer would return.

Dr. Ricardo Gonzalez, Chief of Surgery

“You commit to taking a patient through an operation of this magnitude and there is a one in five likelihood of long-term survival,” said Dr. Ricardo Gonzalez, chief of Surgery at Moffitt. “We can’t predict what will happen with one person. They deserve the chance.”

It’s a chance Morel didn’t hesitate taking. She would do whatever she had to do to live and to spend more time with her children.

“I am not a very religious person, but I had a gut feeling that I wasn’t going to die,” said Morel. “I told everyone I am not going to die from this, this is not going to take me out.”

Prior to surgery, Morel’s care team, which included surgeons, medical oncologists and endocrinologists, decided to start her on chemotherapy. They hoped the treatment would shrink the disease, but if her cancer spread during chemotherapy, it would lower her chances for survival and make surgery less likely.

Morel came in for chemotherapy four days a week for six weeks. “I felt like I was dying,” she said.

Unfortunately, the chemotherapy had little effect on Morel’s cancer. She and her team were now at the point of no return: Was it time to go ahead with the surgery?

“I wanted the surgery from the beginning,” said Morel. “I wanted the cancer out of my body.”

Morel, right, poses with her family

With Morel’s blessing, Gonzalez moved forward with the surgery planning. Because the procedure would require both cardiac and mesenteric bypass, he would need very specific equipment not normally used during cancer surgery. He would also need the help of a cardiac surgeon and transplant surgeon to assist with bypass and the removal of Morel’s kidney, her inferior vena cava and a large portion of the liver. Because of this, the surgery would need to be performed at Tampa General Hospital and assisted by two of its surgeons.

“We talked over it a lot. It’s crucial to have medical oncology and surgical oncology on the same page if you’re going to do complex multidisciplinary therapy,” said Gonzalez. “Tough decisions arise during therapy and during complex operations, and these decisions are shouldered by the team.”

The surgical team also talked the surgery over extensively with Morel, who had never had surgery before. The complex procedure was difficult for her to understand, but it didn’t shake her faith. “I fell in love with Dr. Gonzalez the moment I met him,” she said. “Even though he told me the worst-case scenario that he could lose me on the table, I knew he wasn’t going to let me die. I wasn’t scared at all because I was in the best hands.”

Pushing the Limit

Not only was Morel battling a life-threatening disease, but she also was doing so during the COVID-19 pandemic. Her husband waited for hours in parking lots while she went to every doctor’s appointment alone. And after he dropped her off for her surgery, Morel wouldn’t see him or her family again for three weeks.

She felt anxious, but still not scared. “I remember 10 people coming into the room and saying it was time and I knew in my mind it was going to be OK.”

Morel’s surgery spanned two days. The tumor was situated in the inferior vena cava at the level of the hepatic veins, which drain de-oxygenated blood from the liver into the inferior vena cava. There was also cancer in the vena cava extending from the heart down toward the middle of the abdomen. The inferior vena cava is the large vein that returns blood to the heart from the body.

Surgeons had to transect multiple veins to get through to the tumor and had to be extremely cautious when removing it; if pieces broke off and lodged in the blood vessels leaving the heart to the lungs, it could kill Morel. They also removed her right kidney and 70% of her liver, which was even more difficult because chemotherapy damages the liver and causes excess bleeding. Ideally, surgeons don’t like to remove more than 60% of a cancer patient’s liver, but in Morel’s case they had to push the limit because they had no other choice.

“Removing significant amounts of liver can be challenging in patients after chemotherapy,” said Gonzalez. “They have lower thresholds for liver failure. Removing too much liver can lead to failure and the mortality rate is high in that setting. Taking out just 10% more of the liver than expected and you’re kicking it up a notch.”

After about 11 hours in the operating room, the surgeons decided to pack Morel’s abdomen with gauze to help stop or slow bleeding. They monitored her closely overnight and brought her back into surgery the following day to remove the packing. Then the waiting game began.

“You have a lot of control in the operating room. That's our comfort zone, right?” said Gonzalez. “After surgery, you put somebody in an intensive care unit and things can happen that are outside of anybody’s control, and even with the best treatments possible things can change quickly. Excellent after-care is a must.”

Road to Recovery

Because surgeons removed so much of Morel’s liver, it was the main concern in the early days of recovery. If she went into liver failure, she wouldn’t survive, and when liver function is down, it can have lasting neurological effects.

However, after a few rough and uncertain days, Morel moved for the first time. “After that I thought she’s coming around, she is going to turn this corner and she’s going to do great,” said Gonzalez.

That’s when the struggle to recover began for Morel, who remembers very little from her ICU stay. She moved from the ICU to a regular floor and then to a rehabilitation floor, where she had to push through the pain to get moving. “I didn’t want to do anything except lay in bed,” she said. “But they told me if I got up and did what I had to do, my time there would be shorter, so that’s what I did.”

Dr. Sarah Hoffe, section head of Gastrointestinal Radiation Oncology

Three weeks later, Morel returned home, where she continued rehab.

In order to decrease the chance her cancer will return, Morel started radiation therapy in November. Because her anatomy had changed from the surgery, she isn’t the traditional radiation patient. Gonzalez worked with radiation oncologist Dr. Sarah Hoffe, section head of Gastrointestinal Radiation Oncology at Moffitt, to plan out Morel’s treatment. They fused together her pre-operative and post-operative scans to map out exactly where to radiate.

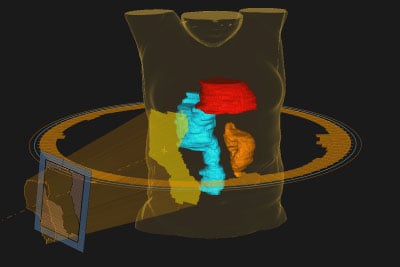

The radiation therapy team used 3D models to plan the treatment. A multi-leaf collimator shapes the radiation beam to hit the tumor (blue) and decrease exposure to surrounding heart (red) and kidney (orange).

“The biggest concern we have is her remaining kidney, so we are keeping the radiation doses low in that area to prevent long term kidney damage,” said Hoffe. “We also have to make sure her liver and spinal cord don’t get too much radiation.”

To make sure the doses are exactly right, Morel is receiving intensity modulated radiation therapy, a very advanced form of therapy that divides the radiation beam into individual beamlets to allow for sculpting the dose so that higher, more effective doses of radiation are delivered to the target areas while minimizing exposure to surrounding healthy tissue. Morel’s treatment will also be guided by imaging with a daily cone-beam CT taken immediately prior to each treatment to identify any organs that may have shifted prior to radiation and verify her position.

Living to the Fullest

While Morel is back to work part time in the business office of a nursing home, her recovery still continues. She has to leave work early some days because of the pain, and struggles with restless leg syndrome while sitting at her desk. She still battles depression, and while she is currently cancer free, she struggles with the anxiety that the cancer could return.

“What if it comes back? That weighs heavily in the back of my mind and it’s something that never goes away,” she said.

But she refuses to let that anxiety overshadow the new chance for life the surgery gave her. She hopes that each day, the weight of cancer feels a little less.

“I feel really blessed that I am still here,” said Morel. “I do have my days where I shut down, but I tell myself I can’t live every day like that. I was given another chance for a reason and I try to live every day to the fullest.”