Moffitt Doctor Brings his Passion to Pakistan

Walking the halls at Moffitt, you see hundreds of health care professionals and some of the most advanced medical technology. For gynecological oncologist Dr. Mian Shahzad it puts things in perspective.

Growing up in a remote village of Pakistan, Shahzad remembers studying on floor mats in school and classmates who often would come to school without shoes. By the time his grandfather was diagnosed with prostate cancer, it had already spread to his spine, leaving him paralyzed and bedridden. His extended family created a home hospice for him, making a schedule to give him care around the clock. He would tell a teenage Shahzad about the lack of compassion from some physicians and absence of proper testing and diagnoses. That’s when Shahzad knew he wanted to become a doctor.

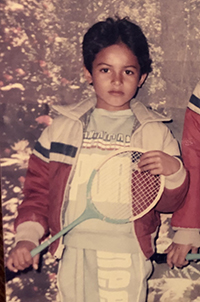

Dr. Mian Shahzad as a child in Pakistan.

When he was 15, Shahzad and his family moved to the United States, and he started working toward his goal. After two decades of school and extensive training, Shahzad became the first Pakistani-American gynecological oncologist. While he started a successful career in the states, he never forgot about his home.

“Only 30 to 40 percent of women with gynecological cancers get to see a gynecological oncologist in the United States,” said Shahzad. “You think that is a low number, but in Pakistan, it’s probably zero.” Instead, Shahzad says women with gynecological cancers in Pakistan are seen by OBGYN physicians, general surgeons or urologists, who do what they can but do not have all the proper oncology training. That, combined with the lack of supportive care and comprehensive post-operative care, results in outcomes that are not as good as they are in the U.S. Shahzad was inspired to push for change.

Two years ago, Shahzad scheduled his first trip to Pakistan to visit hospitals and medical schools. “My first visit was to help make them aware of what gynecological oncology is,” said Shahzad. “They were surprised to hear what it was and what surgeries we do.”

Dr. Shahzad speaks to a group of students.

When he returned to Pakistan this January, Shahzad focused on laying the groundwork for a specialty training program. Since his first visit, the country has acquired one American-trained gynecological oncologist who is training her first fellow, and Shahzad says there is tremendous interest in setting up a larger training program.

Ideally, he says, he would like to help set up a local program that could be overseen by Moffitt or have an international program where doctors could be trained at Moffitt and return to work in Pakistan. He can also envision the two sites sharing tumor board cases.

Shahzad also spoke to medical school students on his trip. “The best part of going there was for them to hopefully have someone to look up to and think that they can do this,” he said. “It shows how far education can take you.”

While Shahzad’s education has taken him almost 8,000 miles away, he will never forget where he came from. He says he sometimes feels a twinge of guilt that he left but is reassured knowing he can actually offer even more help from the position he is in. He plans to continue traveling to Pakistan yearly. He hopes he can keep bringing awareness and build a robust training program for gynecological oncologists who will eventually serve the people there.