Does Intensifying Lymphodepletion Impact CAR T-Cell Therapy?

Before a cancer patient receives cellular therapies such as CAR T-cell therapy, they must undergo a process called lymphodepletion. This involves receiving a short course of chemotherapy to kill T cells, a part of the immune system. Lymphodepletion can effectively prolong the persistence of infused cells and increase the effectiveness of treatment.

A new study led by Moffitt Cancer Center and presented at this year’s American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting aims to understand how changes in lymphodepletion impact allogeneic CAR T-cell therapy for patients with relapsed B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma and B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

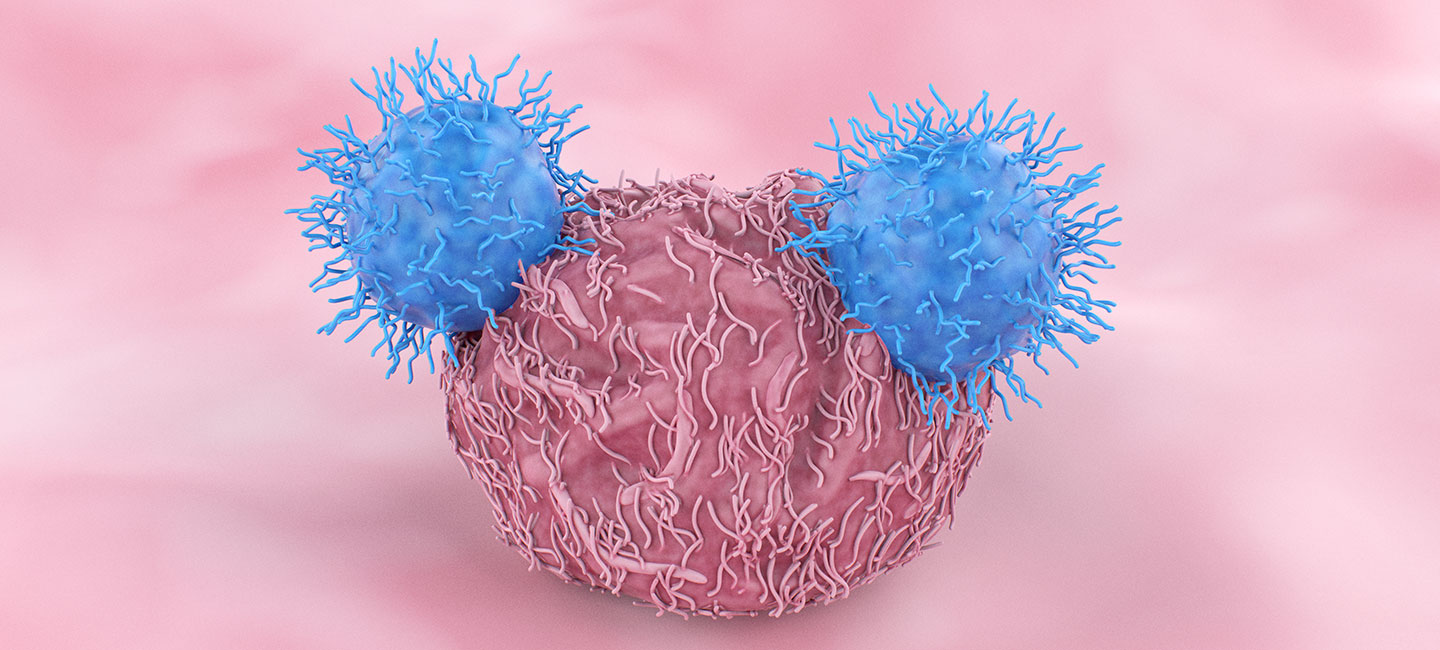

For CAR T-cell therapy, T cells are genetically modified to recognize and kill cancer cells. The therapy can be autologous, meaning the cells come from the patient, or allogeneic, where the cells come from a donor.

Dr. Bijal Shah, medical oncologist, Malignant Hematology Program

“One of the challenges we run into when we talk about allogeneic CAR T cells is that they are foreign to the body,” said Dr. Bijal Shah, lead study author and medical oncologist in Moffitt’s Malignant Hematology Department. “We expect the body to reject the CAR T cells as the immune system recovers. So, the real question is how much of a window do you need for the CAR T cells to grow, expand and do their job?”

During phase 1 of the study, researchers noticed peak CAR T levels were beginning to drop off 10 days after the CAR T-cell infusion as the immune system began to recover. That rapid decrease of CAR T cells was associated with an increased risk for disease relapse.

To see if they could prolong the CAR T cell drop off, researchers increased the dosage and duration of two chemotherapy drugs during the lymphodepletion process. They also used a gene editing tool called ARCUS to modify the CARs to help prevent graft versus host disease and help them better fight the cancer.

After intensified lymphodepletion, patients had measurable CAR T cells at day 28. “It shouldn’t surprise anyone, then, that this was associated with higher response rates across both non-Hodgkin lymphoma and acute lymphoblastic leukemia, including complete response in 56% and 80% of patients respectively,” said Shah.

Many patients on the trial also demonstrated prolonged responses to the treatment, including well beyond six months. This enabled some to go on to receive curative treatments like stem cell transplants.

The study also showed allogeneic CAR T-cell therapy with increased lymphodepletion resulted in better outcomes for patients who had previously undergone autologous CAR T-cell therapy. Shah says the next steps are to build out the trial to focus on these patients to see if they can achieve better results, as well as begin to open trials that offer the treatment to patients in earlier lines of therapy.