Can a Urine Test Change the Standard of Care for Bladder Cancer?

Bladder cancer is a tough disease.

It’s tough to detect.

It’s tough to treat.

It has one of the highest recurrence rates among all cancer types. Depending on which stage the disease is found, there’s anywhere between a 30% to 80% chance it returns in five years. As a result, it’s also one of the most expensive cancers to treat.

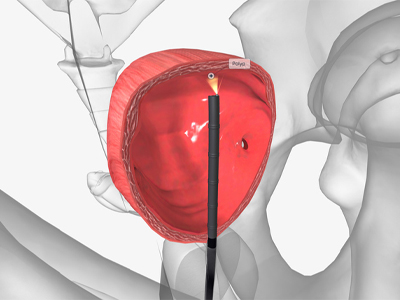

During a cystoscopy, doctors look for abnormal signs or symptoms of disease in the bladder. This has long been the standard of care for detecting bladder cancer.

Most bladder cancers are diagnosed through a cystoscopy procedure, where doctors insert a long, narrow tube through the urethra. There’s a lens at the end that allows them to see inside the bladder and diagnose cancer. Although not usually a painful procedure, the unfamiliar feeling of a cystoscopy can be quite uncomfortable.

Once diagnosed, the patient needs to undergo a second procedure under general anesthesia to have the tumor surgically scraped, and in doing so finding the depth of tumor invasion. Treatment for bladder cancer is dictated by its depth of invasion.

For non-muscle invasive bladder cancer, a urologist will typically scrape away the tumor using an electric loop, along with some of the tissue that’s surrounding the tumor at its base on the surface of the bladder. It’s sometimes followed by instillation of medicines into the bladder to prevent recurrence and progression. This is the “easy” route.

Muscle invasive bladder cancer occurs when cancer cells have spread into or through the muscle layer of the bladder wall.

For muscle invasive disease, the primary treatment is surgery to remove the bladder altogether, along with combined chemotherapy and radiation therapy for selected patients. This means doctors often have to rebuild a patient’s urinary tract, typically done using the patient’s own intestine.

After initial diagnosis of high-grade, high-risk tumors, patients often undergo another round of surgery under anesthesia due to the high likelihood of identifying residual disease. Many patients face multiple surgeries using general anesthesia.

“What we’re typically seeing with our scopes is just the tip of the iceberg,” said Dr. Roger Li, a genitourinary surgeon at Moffitt Cancer Center. “Once we remove the visible parts of the tumor, there are often growths underlying the surface of the bladder that may be invisible. To complete the diagnosis, a second procedure is performed to completely eradicate disease from the base of the initial resection.”

So is there a better, safer and less expensive way to find, treat and ultimately cure bladder cancer? That’s a question that Li and his colleagues at Moffitt Cancer Center are hoping to answer. They believe that urine tests may hold the key.

Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) is an emerging biomarker rapidly gaining momentum in the management of multiple tumor types. The idea is that tumor cells constantly shed their altered DNA into the blood stream, and in the case of bladder cancer, into the urine. Using cutting edge genomic sequencing technologies, the tiny fraction of tumor-shed DNA can be detected within the blood or urine to diagnose cancer. Li and his team are involved with three studies looking at how urinary ctDNA can be incorporated into the management for bladder cancer.

Researchers are hopeful that circulating tumor DNA found in urine can be the key to unlocking the next standard of care for bladder cancer.

In one of their studies, the researchers are using the tumor tissues collected from patients at their initial resection to understand the specific tumor-associated DNA changes. Equipped with this knowledge, the study team and their collaborators create a personalized gene panel and use this to detect tumor-specific DNA within the urine as a surrogate for persistent disease. The ultimate goal is to have enough confidence in the urine test to determine whether or not there is any disease left over in the bladder after the first round of surgery. If the tests prove to be effective, Li says it could help up to 50% of patients avoid an unnecessary surgery and establish the proof-of-principle to use this non-invasive test to detect bladder cancer.

“Because of bladder cancer’s high recurrence rate, patients are mandated for follow-up cystoscopy every three months,” said Li. “Unfortunately, these tests can be misleading, where inflammatory bladder lesions may be mistakenly attributed to cancer recurrence. For patients enrolling onto our studies, we’re using an alternative method to track their cancer journey. The urine test in a way serves as a secondary reassurance that they’re indeed cancer-free.”

Lucia Camperlengo is a research coordinator at Moffitt. Her role is to help identify potential candidates for Li’s studies. She also helps facilitate the collection of blood and urine samples throughout the patients’ treatment journeys.

“The biggest gain from these projects is for the patients to have such a minimally-invasive way of surveying for disease recurrence and progression,” said Camperlengo. “It may sound dramatic, but every single sample to me is such a big deal because it’s one step closer to getting that huge breakthrough.”

For patients with muscle invasive disease, these tests could ultimately be used to determine whether it is safe for patients to avoid bladder removal surgery. According to Li, around 20% to30% of patients with muscle invasive bladder cancer show no sign of disease in their bladder after surgical removal.

“In those patients there’s a critical unmet need to reliably detect minimal residual disease prior to surgery,” said Li. “Based on current diagnostic methods short of removing the bladder, this is simply not possible. The question is can we use the urine to predict whether or not they have disease? If they don’t, can they go on to have their bladders preserved and surveyed for cancer recurrence?”

Over time these studies will be compared against the standard of care to determine whether or not they can be as effective at surveilling and detecting disease. While it will likely be years before a true change to the standard of care, the belief among researchers is that it is only a matter of time before these genomic tests will take over.

“The current standard of care adds so much stress on patients and their families,” said Camperlengo. “These urine tests, to be able to do some of the same things that these surgical procedures do could be so much simpler. It’s inspiring and I feel very lucky to be part of these projects.”