The Long Journey in Search of a Cure

Michelle Shannon lays in a hospital bed, her husband, Russell, sitting in a chair by her side. A cooking show is on the TV, and they laugh about never wanting to eat squid ink pasta. They’re trying to pass the time, patiently waiting for Michelle’s treatment.

It’s not the first time they’ve found themselves waiting. For three years, they’ve waited for the good news that has never come. For the past four months, they’ve waited for this next chance for a cure.

Down the hall, a flat metal box containing a frozen bag of immune cells is taken out of a giant tank of liquid nitrogen. Vapor fills the air, the lab technician wearing giant gloves that look like oven mitts so he doesn’t get burned. A lukewarm bath is waiting. The cells are placed inside, and in just a few minutes they are transformed from a solid frozen mass into a clear, slightly pinkish liquid.

Michelle Shannon, with her husband Russell by her side, prepares for her TIL infusion that has been months in the making.

The bag is filled with only 55 milliliters of liquid, but that liquid contains hundreds of millions of tiny cells. This lifesaving material has been on an extraordinary journey over the past four months. Harvested from inside Michelle’s body and transported across the street from Moffitt McKinley Hospital to the lab on Moffitt’s McKinley Campus. Prepared, frozen, combined with antigens gathered from Michelle’s blood and bathed in a mixture of proteins to encourage the immune cells to grow. Then transported 2 miles to Moffitt’s main campus for infusion.

On Jan. 12, 2024, the journey comes to the most important end. After their final thaw, the cells are carefully carried about 200 meters from the holding lab area to Michelle’s room on the cellular therapy patient floor.

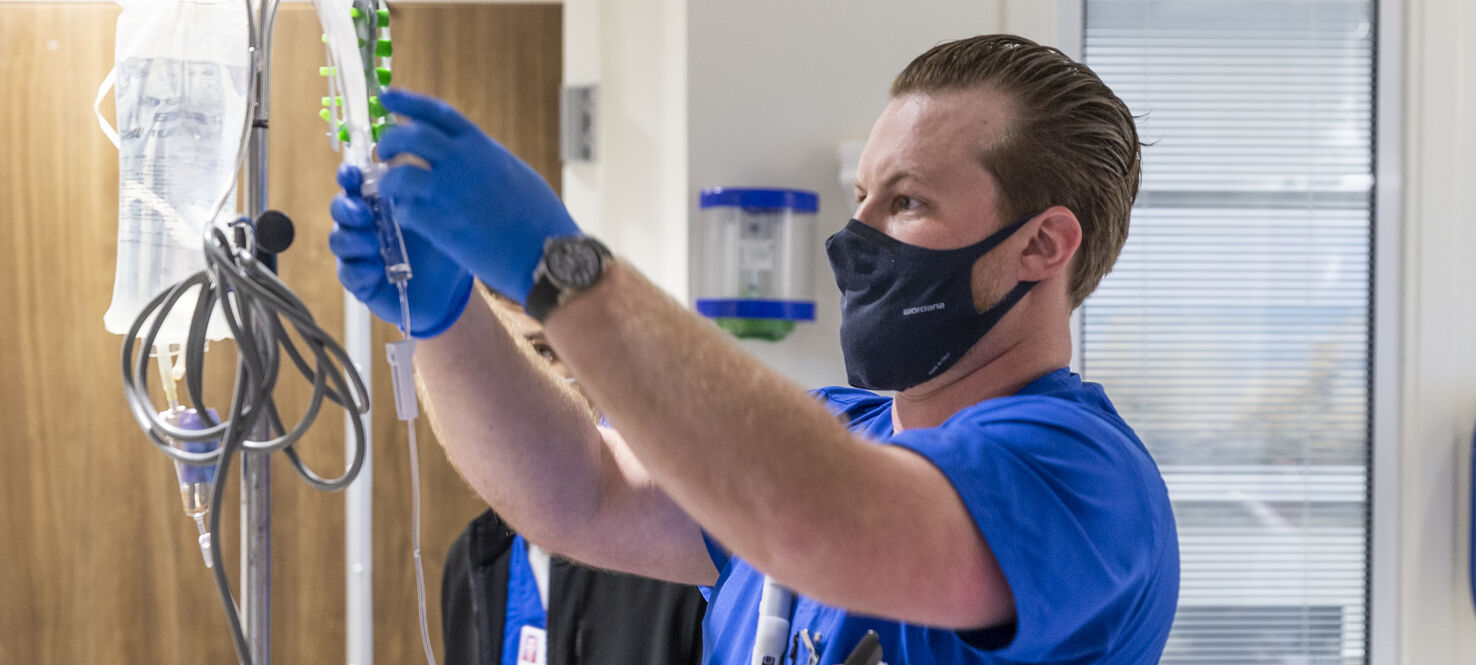

“It’s showtime,” Michelle’s nurse says as he hangs the bag of cells and connects it to her central line.

A chaplain walks into the room, and Russell bows his head. They pray these cells will be the cure the 61-year-old needs. The nurse opens the line and liquid begins to slowly drip, traveling down into Michelle. Russell grabs her hand. They both shed tears — happy and scared tears, they say — and wait for the bag to empty. When the bag finishes, the nurse swishes anything that may be remaining with some water to make sure Michelle gets every last drop. Then another bag is brought in.

There are three bags of immune cells, and it takes about an hour for all of them to be infused into Michelle. Surgically removed from her lung months before, the cells have made their way back home. They now are on a mission to seek and destroy the cancer that has evaded so many other treatments over the past three years.

‘The Fear of the Unknown’

In December 2020, Michelle started having trouble with her vision. A visit to the optometrist led to a referral to a specialist, who confirmed a mass protruding into the iris of Michelle’s left eye. She had uveal melanoma, a rare type of cancer that occurs in eye tissue. The American Cancer Society predicts only around 3,400 people in the United States will be diagnosed with eye cancer in 2023.

“I was totally surprised,” Michelle said of her diagnosis. “There is always the fear of the unknown because you don’t know what to expect because you have never been in that position before and you haven’t heard of that type of cancer before.”

She immediately started a type of radiation treatment called plaque therapy at a hospital in Miami, more than 200 miles from her home in Lake Wales, Florida. In this approach, a small carrier the size of a bottle cap containing radioactive “seeds” is surgically placed over the eye where the tumor is. It helps more precisely deliver radiation to the affected area, shielding nearby healthy tissue. The treatment left Michelle with intense headaches, eye pain and light sensitivity. She works in payroll for a golf course in Lake Wales and had to work with all the lights off in her office. In 2022, she decided to have her eye removed and replaced with a prosthetic.

Shortly after the surgery, Michelle learned the cancer had spread to her liver and lungs. She transferred her care to Moffitt Cancer Center and joined two different immunotherapy clinical trials over the next year. Neither was successful at keeping her cancer at bay.

“It’s mind-blowing because you get your hopes up and then you get dashed whenever the results come back that aren’t so favorable,” Michelle said. “I try to keep my faith, but it’s intimidating with all the information. You have to try this and try that and figure out this step and that step. Sometimes it’s overwhelming, but we will get through it. We will wade our way through the waters.”

In the summer of 2023, Michelle’s team presented her with another clinical trial involving tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte, or TIL, therapy. This approach harvests naturally occurring T cells that have already infiltrated a patient’s tumor, activates and expands them in a lab, then reinfuses those cells into the patient to seek out and destroy cancer.

Willing to do whatever it takes, Michelle enrolled.

‘We Are Not Going to Stop Here’

Although TIL was a novel treatment option for Michelle, the National Cancer Institute began studying the therapy in the 1980s. In 2009, Moffitt researchers visited the institute to learn the protocol, and Moffitt became the first cancer center outside of the institute to offer TIL to melanoma patients. Since then, Moffitt has opened eight TIL trials, treating about 100 patients. Led by Moffitt cutaneous surgical oncologist Amod Sarnaik, MD, a trial for patients whose advanced melanoma failed to respond to other treatments reported a 38% response rate to TIL, promising results for patients who have run out of treatment options.

That data helped lead to the FDA approval of the first TIL therapy for advanced melanoma in February 2024. Trials have shown the treatment can be successful in multiple types of melanoma, including the more difficult-to-treat mucosal melanoma, acral melanoma — which is commonly found on the palms of hands and soles of feet — and uveal melanoma.

During the cell manufacturing process, cells are initally frozen for preservation. They are periodically thawed and mixed with antigens and proteins to promote growth.

The goal of the treatment is to harness the power of the body’s immune cells called lymphocytes, which include T cells. It begins with surgery to remove some of the patient’s tumor. Once in the lab, the tumor tissue is divided into smaller bits and the samples are bathed in a protein mixture that encourages the cells to grow. Surviving T cells are tested to see which react most strongly to the tumor. Those are then multiplied by the billions to be infused back into the patient to attack the cancer.

Prior to the FDA approval, Moffitt was one of only five cancer centers nationwide that could manufacture a patient’s TIL cells for clinical trials, thanks to its multimillion-dollar Cell Therapies Core on Moffitt’s McKinley Campus. Since the treatment’s approval, all cell products are manufactured at an offsite facility to ensure standardization and safety.

Now that the first TIL product is approved, it’s time to find ways to optimize the treatment. More trials are being conducted to find ways to cut down on manufacture time and create a better product with a higher success rate.

“We are not going to stop here. We aren’t going to be satisfied with what we have now. We are greedy in terms of wanting to get better responses for patients,” Sarnaik said.

Michelle Shannon’s trial is one of the newer TIL trials that aims to create an even more responsive treatment. In addition to harvesting T cells from the tumor in her lung, antigen-presenting cells were collected from her blood during a process called apheresis. Those cells are used to stimulate TILs that have been grown to help hand select the most responsive TILs. The nonreactive TILs are discarded, and the responsive TILs are then expanded before being infused back into the patient.

“You always hope you’re on the breakthrough, the one that will work,” Michelle’s husband, Russell, said. “But even if it doesn’t work for her, it will help others.”

‘I Feel More Hopeful This Time’

Five days before her surgery in September 2023 to remove the T cells from her lung tumor, Michelle drove the hour and 15 minutes from her Lake Wales home to Moffitt. She had an entire day of appointments ahead of her. She met with the anesthesiologist and cellular immunotherapy doctor. She needed blood work, a brain MRI, heart echo, full body scan and a pulmonary function test.

She was nervous about what’s to come but tried to focus on the positives in her life. She had just returned from her happy place, a hunting cabin in Varnville, South Carolina, where she took in the sunrise alongside the chirping birds. She had the support of her family — Russell, her husband of 42 years; son Christopher and daughter Amber; and four grandkids under 10.

“I feel more hopeful this time,” Michelle said. “The first treatment you are scared to death, and then it’s heartbreaking when it doesn’t work. But the doctors gave us hope, and there are other things we can do if this doesn’t work.”

A surgical team, lead by thoracic surgeon Jobelle Baldonado, MD, removed a portion of Shannon's lung tumor. The tumor piece is transported to a lab where T cells are extracted to begin the cell manufacturing process.

She brought that same attitude to Moffitt McKinley Hospital the following week. She and Russell were calm, ready to get the process started. In the operating room, the thoracic surgeon removed about a 5-inch piece of Michelle’s lung tumor. Sarnaik, the principal investigator for her trial, joined them in the operating room and dissected the tumor into three pieces with a scalpel and tweezers. One piece was put into a specimen cup filled with red liquid to be transported to the Cellular Therapies Core to begin the TIL process. Another piece was saved for further research. The rest went to pathology for evaluation.

Michelle was wheeled into the recovery room, and the waiting game began. Because her trial involved additional steps and her manufacturing process had some setbacks, it took longer to manufacture her TIL. The newly FDA-approved TIL product takes on average eight to 12 weeks. She waited four months for hers.

‘You Can’t Stop Living Your Life’

After Christmas, Michelle got the call she had been waiting for: Her cells were ready. She had squeezed in another trip to the hunting cabin for Thanksgiving and spent Christmas surrounded by her grandchildren. She would start 2024 off with a new “birthday,” the day she is reborn from a cellular level.

First, Michelle underwent five days of induction chemotherapy. The treatment reduces the number of circulating lymphocytes in the body to create a more favorable environment for the TIL. After two days off, she returned for her TIL infusion. Her cancer had grown while she waited for her cells to be ready, but she had held onto hope that this new army of cells would do its job.

Zachary Sannasardo, a cell technologist, thaws Shannon's cells before infusion.

After the TIL infusion, Michelle got a drug called interleukin-2 every eight hours for up to six rounds. It helps encourage immune cells to grow but comes with intense side effects such as fevers, rigors and nausea. A patient only takes as many doses as they can tolerate. Michelle pushed through all six.

“It was actually better than I expected,” she said. “Now keeping my fingers crossed that it worked.”

She was ready to go home after five days. Although she had to travel back to Moffitt for daily checkups and injections to help boost her immune system, she said it was worth it to be sleeping in her own bed and getting back to her routine. Because the treatment depleted her white blood cell count, she left the hospital with a giant bag of medications — antibiotics, antibacterials and antifungals to protect her against infection.

Six weeks after her TIL infusion, Michelle and her husband, Russell, were relieved to find out her scans showed no new tumor growth.

The waiting game began again, this time six weeks until a scan to find out if the TIL was showing early success.

When the time came in mid-February, Michelle had lost her hair from the chemotherapy and her stomach was covered in bruises from the immune-boosting injections. But on the inside, she was the same strong and determined woman who enrolled in the trial almost six months before.

She was overjoyed when the doctor told her the scan showed no new tumor growth. It’s too soon to tell if the treatment will be her cure, but it’s a great start. She will continue to wait and continue to hope.

“You always have the thought how is it going, how is it going to turn out, but you can’t stop living your life,” Michelle said. “I am glad I went through this. We are really hopeful.”

This story originally appeared in Moffitt's Momentum magazine.